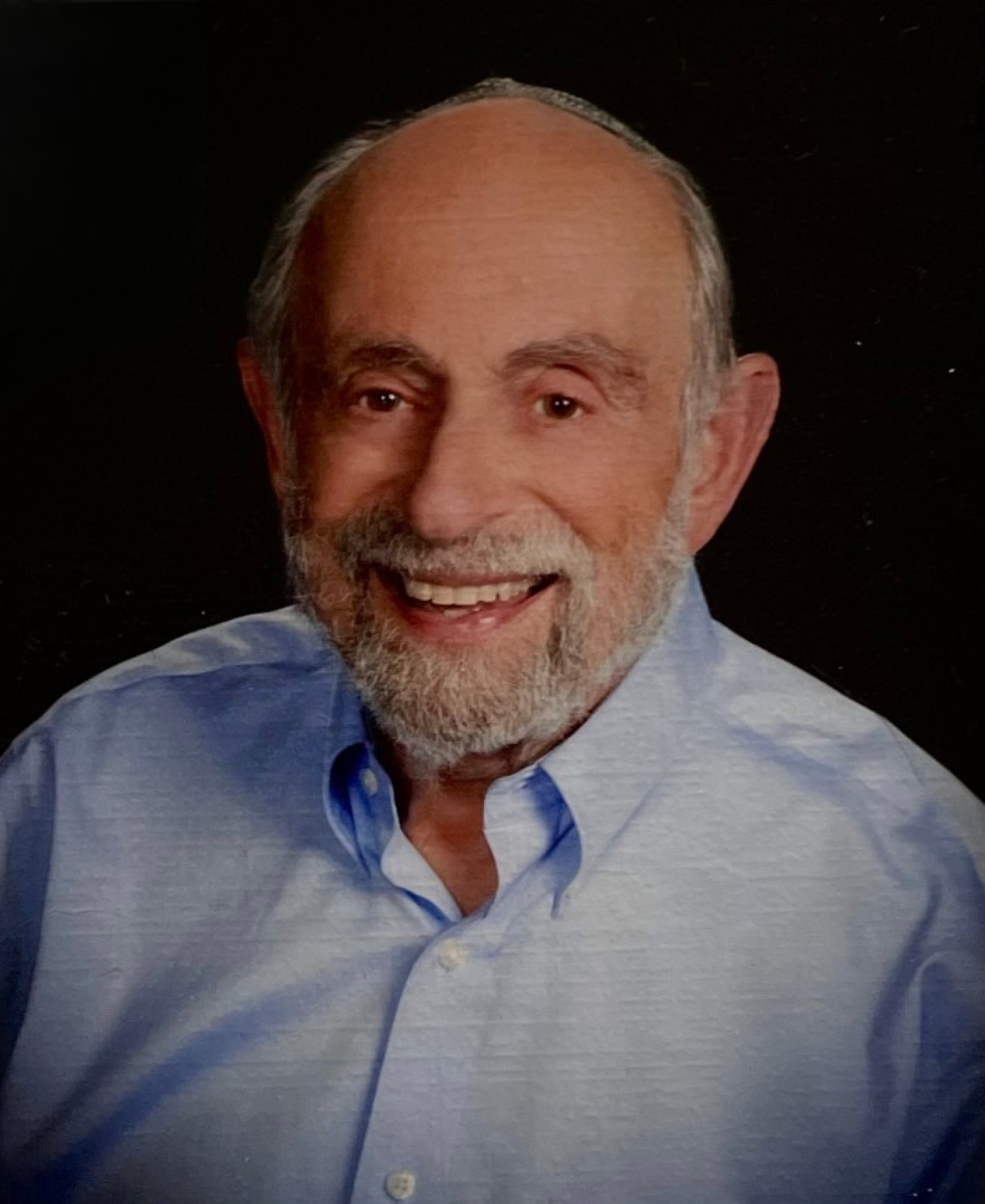

Dr. Edward A. Stern

Dr. Edward A. Stern was a distinguished physicist and emeritus professor at the University of Washington, internationally recognized for his pioneering contributions to the development of the X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (XAFS) technique. Beyond his scientific achievements, he was a tireless activist and community leader who championed human rights, Jewish life, and academic freedom—from aiding Soviet scientists to founding Congregation Beth Shalom in Seattle. Guided by his deep commitment to Tikkun Olam, Dr. Stern devoted his life to advancing knowledge, justice, and compassion, leaving a lasting impact on generations of students, colleagues, and communities worldwide. You can listen to Dr. Stern's oral history interview and his collection of papers at UW Special Collections.

The Early Years

Edward Abraham Stern was born on September 19, 1930, in Detroit, Michigan, the second of three sons of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. His father, Jack Stern, was the son of a pharmacist in St. Petersburg, Russia, and the grandson of a rabbi in Lithuania—where Jack spent much of his youth—getting his Jewish education at his grandfather’s yeshiva. Ed’s mother, Rose Kravitz, was raised in a small village near Grodno, now in Belarus, but during her childhood part of Russia, then Poland.

They arrived in America at opposite ends of the continent. Ed's father had been exiled to Siberia and escaped to Japan in 1917, eventually making his way to, of all places, Seattle—staying for just a couple of days before heading cross-country to Kentucky, where he had an uncle in the junk business. When that uncle pressured him to marry his daughter, Jack decamped once again, this time to Detroit, where he got work as a hand engraver—a skilled craft in those days—in Detroit. Rose took a more traditional route to the United States, entering in Boston, staying for a short while in New Haven, then settling in New York, where she worked in a textile sweatshop. She had a sister in Detroit, and while visiting the city met Jack, and following a six-week whirlwind romance they were married in the mid-1920s.

The Stern family lived in a Jewish ghetto in Detroit, a city infected by the notorious antisemitism of Catholic priest (and radio personality) Father Coughlin and automobile tycoon Henry Ford. Their neighborhood bordered a Catholic area, and, in his oral history with the Washington State Jewish Historical Society, Ed recalled frequent, violent confrontations with his Catholic contemporaries.

“I got beaten up several times. I gave some beating up in return. It was actually a very traumatic experience, all this antisemitism against us. It has affected my behavior and my feeling towards defending Jewish people [ever since].”

The Stern family relocated to Los Angeles when Ed was 15. When he was a junior in high school, Ed was accepted to the California Institute of Technology (or Caltech) in Pasadena, where he majored in engineering, while continuing to live at home. In Los Angeles, his parents helped found their local synagogue, and Ed was the president of the synagogue’s youth group. Finishing his undergraduate studies, he continued at Caltech as a graduate student in physics and helped organize a Jewish student group, through which the Jewish members of the all-male student body arranged dances with Jewish sororities at USC and UCLA. It was at one of these dances that he met his future wife, Sylvia Sidell, a Seattle native who had transferred from the University of Washington. That was in 1953; they were married on October 30, 1955.

“His mother was a force of nature," his eldest daughter Hilary remembers. “Even though she didn’t have the opportunity to go to school until she immigrated as an adult to the US, she made sure that her sons did their homework and got good grades. She used to tell me all the time that I knew her, ‘You have to get an education. It’s the only thing they can’t take away from you.’ Her eldest, David, became a radiologist, and her youngest, Leon, an engineer. My father, the middle son, became a physicist and a professor."

Physicist and Family Man

Dr. Edward A. Stern received his PhD from the California Institute of Technology in 1955 and continued his work there as a postdoctoral fellow in metallurgy through June of 1957. In 1957, Dr. Stern was hired by the University of Maryland as an Assistant Professor and moved his family to College Park, Maryland. In 1961, he was promoted to Associate Professor at the University of Maryland. In 1963, he moved his family to Cambridge, England, for a sabbatical year while he was a Guggenheim Fellow at Cambridge University. When he returned to the University of Maryland, he was promoted to full professor. As the children got older, Dr. Stern and his wife, Sylvia, wanted to move their young family to the West Coast so it would be easier for them to visit their families in LA and Seattle. Dr. Stern was offered a full professorship at both UCLA and the University of Washington; he chose the UW in Seattle because his daughter, Hilary, suffered from allergies and asthma attacks in LA. In 1965, he started as a full professor at the University of Washington.

As an academic, he moved so much during the early part of his career that all three of his daughters were born in different cities. Hilary was born in Los Angeles in 1957; Shari was born in Washington, D.C. in 1961; and Miri was born in Seattle in 1965.

In 1970, Dr. Stern moved his family to Haifa, Israel, where he spent his second sabbatical year as a Senior Post-Doctoral Fellow at the National Science Foundation at the Technion. In 1985, he returned to Israel for his third sabbatical year as a Fulbright Fellow at The Hebrew University in Jerusalem. During these years in Israel, he collaborated with Israeli scientists, some of them becoming lifelong scientific collaborators and close friends.

Dr. Stern would spend most of his work life at the UW as a professor until 2000 and as an emeritus professor thereafter. In his 35-plus years at UW, he taught countless classes and innumerable students, and focused his energies on the development of Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure, or EXAFS. His graduate students went on to prestigious jobs at US universities and research institutions.

Asked to sum up his career, Dr. Stern once said, “I was always interested in figuring out how things worked. When I was in high school, my mother asked a rich uncle to give me advice on a career. He told me to study mechanical engineering, which I did at CalTech as an undergraduate. I then got a degree in Electrical Engineering, but I knew that my true interest was in understanding how the world worked. So, I switched to Physics for my PhD and decided to follow my interests, even if it didn't lead to riches.”

His UW colleague, Dr. Gerald T. Seidler, explained Dr. Stern’s work thusly: “Early in his career, Dr. Edward A. Stern worked with his graduate student, Dale Sayers, and a Boeing physicist, Farrel Lytle, to correct a deep misunderstanding about the interaction of x-rays with matter, and in the process give the first theoretical description and also the first practical applications of a technique called Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure, or EXAFS for short. Dr. Stern and his collaborators proved that the absorption spectrum of a material in the X-ray energy range, as shown in EXAFS, could be used to identify the element-specific packing of atoms. This new ability to study local structure around an element of choice was revolutionary, and stood apart from the prior use of X-rays in structural analysis by scattering, a method that requires crystalline periodicity and averages over all atoms in a system, no matter their place on the periodic table.

The development of EXAFS, both in initial work by the team of Stern, Sayers and Lytle—and also in the decades of subsequent work by Dr. Stern, collaborators, and many other scientists around the world—opened completely new technical directions in numerous fields of chemistry, materials science, and environmental science, and even in a key problem for international relations: forensic studies to support efforts toward nonproliferation of nuclear weapons. Throughout this effort, Dr. Stern remained a leader in the field, organizing workshops, creating improved analysis methods, publishing more than 200 papers, and developing and operating equipment at large particle accelerator facilities that expanded the technical capabilities and scientific reach of the EXAFS method. EXAFS is now regularly used on materials as diverse as sediments from deep in the ocean, natural and artificial proteins for photosynthesis, and dust captured from the tail of a comet and then returned to Earth."

Dr. Seidler concluded: “Dr. Stern’s central role finds him considered as the intellectual grandfather of EXAFS, a recognition reinforced by the decision of the International X-ray Absorption Society to name their career achievement award in his honor.”

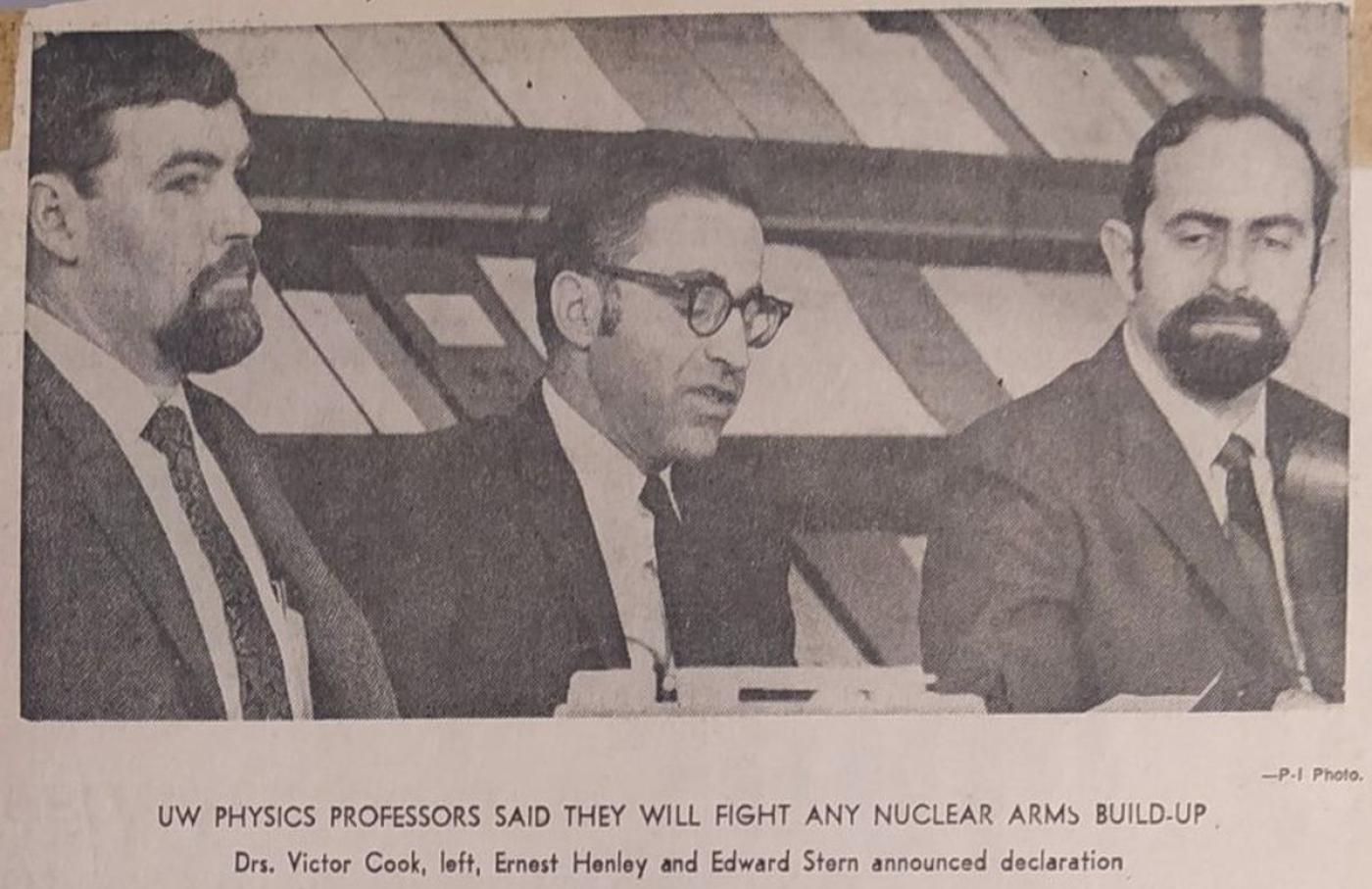

A Voice for Peace and the Oppressed

In 1968, when Dr. Edward A. Stern was a young scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle, he joined with other scientists to question the logic of the arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union, arguing against the Pentagon's planned location of ABM missiles in Seattle. He advocated for a negotiated solution to national security rather than inflaming the arms race by spending more and more money on military hardware. His tireless lobbying, organizing, and public speaking helped defeat the Pentagon’s plans to locate ABM missiles at Fort Lawton, paving the way for Fort Lawton to be given back to the city so that it could turn the former military base into Discovery Park. His status as a respected physicist added weight to the arguments of a loose coalition of citizens and local politicians who opposed the Pentagon and won.

In 1973, Dr. Stern became intensely interested in the plight of Jewish scientists in the Soviet Union, whose requests to emigrate to Israel had resulted in harassment, oppression, and an inability to work in their chosen professions. These scientists, and other Jews who were refused permission to leave the USSR, became known as “Refuseniks.” As it happened, around this time, a Russian mathematician who was traveling in the United States visited the University of Washington, and she told Dr. Stern that it was “helpful to telephone these people, the Refuseniks, and talk to them, and show them support that way,” Dr. Stern explained in an interview with Mildred Rosenbaum for the WSJHS in 1997. “That was a complete surprise to me, because, first of all, I didn't think that I could call the Soviet Union, particularly people who were being ostracized by the Soviet authorities. I was also afraid this might do some harm to them, if I talked to them under such circumstances. She assured me this was not the case, and she even gave me a phone number to call up Mark Azbel, a Soviet Jewish scientist.”

Before calling, Dr. Stern came up with the idea of offering Azbel, a fellow physicist, and his colleague, Alexander Voronel, visiting professorships at UW. Once he secured the university’s agreement, he called Dr. Azbel and discovered that he, Dr. Voronel, Dr. Victor Brailovsky, and three other scientists were in the midst of a hunger strike to protest their situation. “This hunger strike was something that they were doing out of desperation,” Dr. Stern told the WSJHS, “because they wanted to get some publicity for their plight. They had applied to go to Israel, had lost their jobs, and were in a state of complete isolation from Soviet society. They therefore banded together among themselves, but felt, and expressed this point very strongly, that it was necessary to publicize their plight outside of the Soviet Union, because this would give them protection: anything that would happen to them would be publicized in the West. So I became, by just this chance timing, one of their main conduits of information to the West.”

Dr. Stern also contacted U.S. Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington State, who was working on the Jackson-Vanik Amendment—a law that would economically sanction countries like the Soviet Union that denied citizens freedom to emigrate. Dr. Stern told Senator Jackson about the scientists’ hunger strike, and his concern that they might do lasting damage to their health. Senator Jackson asked Dr. Stern to tell them their message had gotten through, and with this encouragement, they were able to call an end to the hunger strike after 15 days. “Senator Jackson really impressed me in his support of the Soviet Jews. I could see that in his case, it was just not a political act, but it was a really emotional, personal act. I remember telling him some of the comments that my Russian contacts said, through the telephone conversations I had with them, about how much they needed his help, needed support, and he was just emotionally moved by that.”

After the hunger strike ended, Dr. Stern continued to have regular phone conversations with these and other Jewish scientists in the USSR, and tapes of those conversations are in the WSJHS archives. A few months later, there was an international scientific conference in the Soviet Union, which Ed attended, accompanied by Sylvia. He and some of his colleagues attempted to pressure the Soviet authorities to allow the Refuseniks, who had been ostracized from the scientific community, to attend the conference, and while this was unsuccessful, Ed was able to meet the scientists he had spoken to by phone while he was in the USSR. He also met the legendary dissident and nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov, who lived in a small apartment in Moscow.

The trip had another benefit for Dr. Stern: it allowed him to visit Leningrad, where his father had been born. "It was an emotional experience to walk along these streets around where my father lived. It helped explain to [the Soviet scientists] why I was so emotionally involved in this issue. Because of my origins, I could have been in the Soviet Union, in the situation that the Refuseniks were in. They were almost exactly my age. I was born in 1930, Voronel was born in 1931, and Azbel was born in 1932. So I had a strong identification with them, because really, just by the luck of fate, I could have been in their situation. So I really felt driven to try to help them.

“That's something that I'm very proud of, because I felt that I personally may have saved some lives, or certainly saved a lot of pain for some of the scientists.”

Throughout his time in the USSR, Dr. Stern was under surveillance by the KGB, though he was never approached by them. Upon his return to the US and for the following ten years, Dr. Stern did as much as he could to publicize the plight of the Refuseniks, including meeting and corresponding with many politicians in Washington State and Washington DC. The Soviet authorities took notice and were not pleased with him. “The Novosti Press Agency [a state-run news organization] wrote an article about me that said I was a reactionary Zionist, and better known for my reactionary Zionist activities than for my activities as a scientist, and I said I considered that a terrible insult, because I'm not known anywhere as a reactionary Zionist except in the Soviet Union. But, of course, it was actually a great compliment, because it indicated that I was having an impact on the Soviet authorities, that they really noticed me, and I was being successful. Other evidence that I had that I was successful was that I wasn’t allowed to enter the Soviet Union any longer.”

Sylvia also did her part, raising money for the refuseniks from local synagogues and Jewish institutions, writing articles for the Seattle Times about their experiences in the USSR and giving public talks for the Jewish community, which were reported on in the Jewish Transcript. Thanks in part to the work of people like the Sterns, the Refuseniks were eventually allowed to leave the USSR for Israel. In later years, Dr. Stern visited many of them in Israel and they visited him in Seattle.

In the Seattle Jewish Community

Throughout his life, from his childhood in Detroit to his college days in Los Angeles to his career as a university professor in Maryland and Washington State, the great constant in Ed’s life was his commitment to Jewish values. He met his wife Sylvia through a Jewish social group he helped start in graduate school, was one of the founders of his synagogue in Seattle, worked tirelessly for the freedom of Refuseniks in Soviet Union, and was a leader of the Jewish community at the University of Washington for 50 years.

Ed’s involvement in the Seattle Jewish community began as soon as he and his family moved here in 1965. Upon their arrival, the Sterns became members of Herzl Congregation, a Conservative synagogue. Ed served on the board of directors and was also active on the school board. In 1968, when Herzl decided to move the congregation’s location to Mercer Island, the Sterns and other members of the congregation decided to start a new synagogue that would remain based in Seattle, which ultimately became Congregation Beth Shalom.

Ed was chosen to be the head and first chair of the community’s religious school. Over the years, each of the Sterns’ daughters had their Bat Mitzvahs at Beth Shalom, and each of them moved forward equal rights for girls due to Ed’s advocacy. Hilary had the first bat mitzvah at Beth Shalom on a Saturday morning. Previously girls at Beth Shalom had their bat mitzvahs on Friday nights. Shari was the first female to have an aliyah and read the maftir. Miri was the first female to chant directly from the Torah. Every time he battled for his daughters to be treated the same as boys—and now girls and boys and women and men in the Conservative Movement have exactly the same rights and obligations.

Congregation Beth Shalom was initially located in a rented former school building at the Blessed Sacrament Catholic church in the University District, where both services and school were held. After several years, it was decided that the congregation should own its own home, and they purchased a building from the Unitarian church. Up until this time, Congregation Beth Shalom had been using a borrowed Torah, but that changed when Ed’s mother made a generous donation that allowed the congregation to acquire its own Torah on August 8, 1976.

“My father had passed away the year before,” Ed remembered in his oral history. “He was a yeshiva bocher in his youth. He was greatly influenced by his studies in the Talmud and the Torah, but he himself didn’t pursue that because he felt that the religious aspects of it were not appropriate for modern-day living, and one had to also learn modern-day things. But he would always quote things from the Talmud and the Torah; he was very learned, at least compared to me. So, our family felt this would be a very fitting thing to donate a memorial to my father, and also, the congregation really needed a Sefer Torah, so we were really very pleased when we could give this donation.”

As a professor at the University of Washington as well as an active Hillel board member in the early 1970s, Ed was well acquainted with many of the school’s Jewish students. One point of contention between students active in Hillel and those who weren’t was the latter group’s feeling that Hillel wasn’t aggressive enough in responding to antisemitic propaganda on campus. As a result, they founded what would eventually become the Jewish Information Society, and asked Ed to be their faculty advisor.

“This group started off as the Israel Action Committee. It was a very effective group, and had a lot of very active Jewish students. There was a lot of contention between the Israel Action Committee and the organization of Arab students because of obvious contrasting ideas of what was happening in the Middle East. In 1975, they changed its name to the Jewish Information Society, because they wanted to get away from this sort of propaganda aspect of what was happening, and to give more background information about Jewish culture, Israel culture, and put on a discussion of the right of Israel and the Jewish people to have their own state.”

Even as he advised the Jewish Information Society, Ed continued to be involved with Hillel, and was honored to be the organization’s president from 1982 to 1985. Under Ed’s leadership (and with a donation from Seattle philanthropist Sam Stroum), Hillel hired its first full-time director of student activities. He also led the effort to make UW’s Hillel a statewide organization, helping to organize Jewish groups in other state universities. Ed also helped bridge the differences between the Jewish Information Society and Hillel, a highlight of Ed’s tenure as a leader of the campus’s Jewish community.

Ed was also involved with two other very important Jewish projects on the UW campus: He helped organize his fellow Jewish professors at the UW to found the UW branch of American Professors for Peace in the Middle East and he helped found the UW Jewish Studies Program.

The late Dr. Edward Alexander, the first Chair of the Jewish Studies Committee, remembered Ed's impact on Jewish life at the UW in these written remarks prepared for Ed's funeral in May 2016:

"Ed was among the founding fathers of the UW Jewish Studies Program. He had been a member of the original Hillel Jewish Studies Committee of the late sixties, which also included [Hillel] Rabbi Arthur Jacobovitz, Neal Groman, and Leo Sreebny. When the group received official recognition from Dean George Beckmann in 1971 (and I was conscripted to be its chairman) Ed was the only person outside of the humanities and social sciences faculty to serve on it. He was invaluable not only for his formidable brain and vast knowledge, but also for his unique diplomatic ability to keep the sometimes irascible Rabbi Jacobovitz in check.

Since Ed, like the rest of us involved in the Jewish Studies project, has been consigned to the Orwellian memory hole by a generation that suffers from historical amnesia, I feel it important to recall all this. Without him, I doubt that the University of Washington would now have either a Jewish Studies Program or a contingent--small to be sure--of faculty willing to undertake the defense of Israel against its manifold academic and journalistic slanderers. He certainly exercised a great influence over me, both as a loyal friend and a kind and patient advisor."