I grew up in Detroit, Michigan, on what was then the edge of the Jewish community, which was centered around Dexter and Davison. We lived about a mile from there. My parents were very left-wing and strongly identified as being Jewish—that was very important to my mother. But they were very opposed to organized religion. I didn’t have a bat mitzvah, and I didn’t enter a synagogue or temple until I was an adult. We were what I have come to think of as culturally Jewish. We believed in the things that Jews have generally stood for, which is equal rights and various other things like that, but were not religious in any traditional sense.

My father was not educated. My father was a very interesting person, who was orphaned when he was about thirteen, and he and his older brother, who was then about fifteen, traveled across the United States, hitching rides, spending nights in jail when they were picked up, and then joined the army. So my father was sixteen, I think, when he joined the army. His older brother was eighteen, lied and said he was twenty-one, and he would sign for my father. But what was so interesting to me and so unusual, was that World War II and the Holocaust were not my parents’ major preoccupations. The war that was important to them was the Spanish Civil War, where my father, along with many young Jews around the world, went to fight against Franco. He was in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. So that was what was important to them, and that was what my father was always the most proud of. So my father joined the American Army before World War II, and wasn’t educated. He had a bar mitzvah before his mother died in Brooklyn, but his parents are buried in a cemetery in Brooklyn under different names. Later he sold aluminum siding, had his own company for a while, and then went to work for one of the big remodeling people in the Detroit area. And my mother was very educated, very highly educated. When I was growing up, she went back to school to get a Masters Degree in Early Childhood Education. She was a nursery school teacher, and then taught at Wayne State University College of Nursing, in child development.

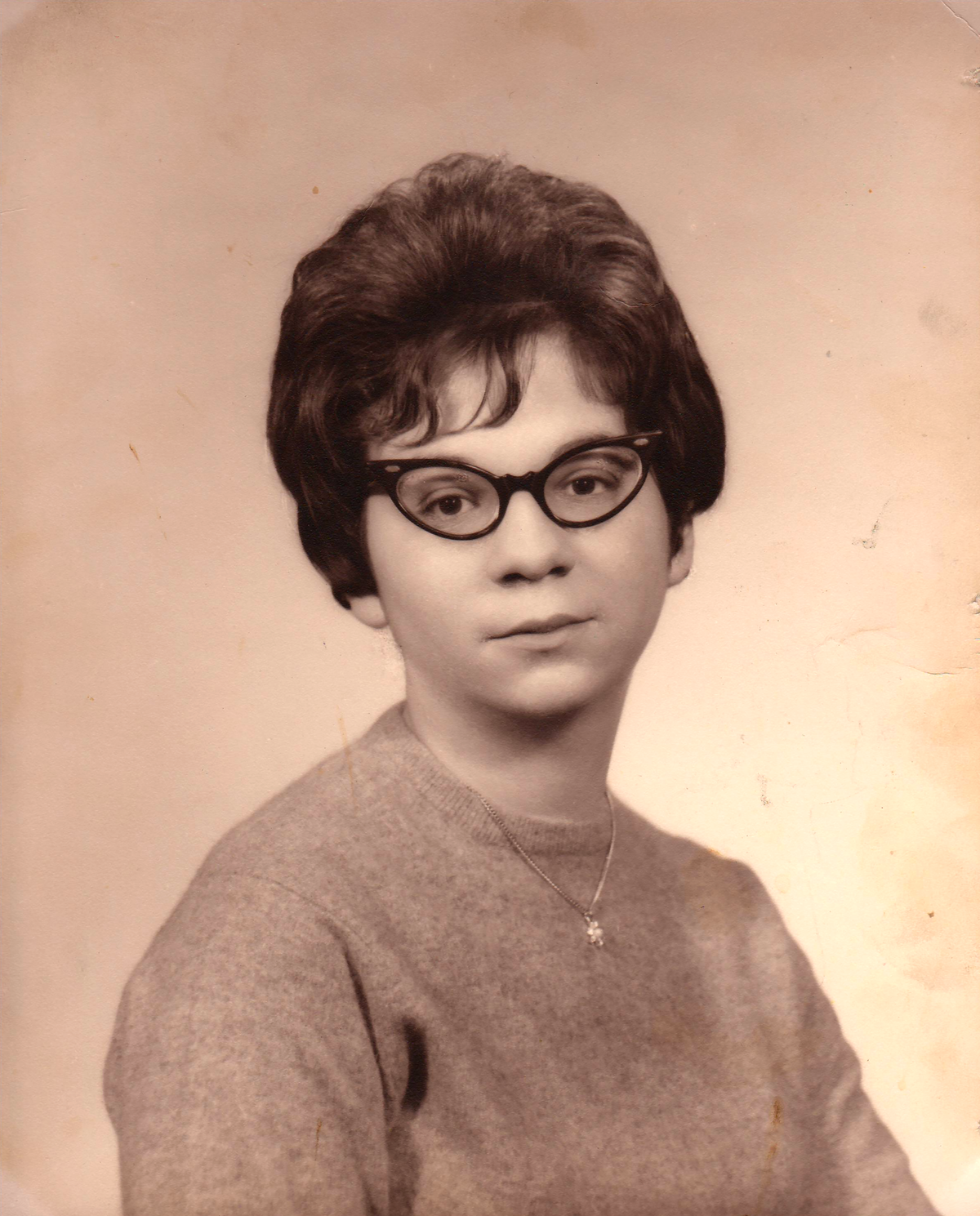

I was always a big reader. My parents passed on to me some great things about the world, but they were not happy people, and for me it was not a particularly happy place, living with them. So I spent all my time at my local public library. I would go there every day after school. I would ride my bike Charger--I was one of those kids who named everything in my life; Charger was my bicycle - and I just grew up at that library. And those librarians, I have to say, were the nicest, kindest people to me, in my childhood. I remember them with great fondness, and I became a librarian because I saw what reading could do, and how it could give you the opportunity to be anyone, and to go anywhere, and to do anything. I wanted to do good in the world, and I wanted to give that gift of books and reading to other children. So I knew when I was ten that I was going to be a children’s librarian when I grew up, and I was. I had one little detour in college, when I got very interested in transformational grammar, which Noam Chomsky was then teaching at MIT. And I thought "Oh, maybe I’ll go to MIT and get a Ph.D in English Linguistics," which would have been a terrible, terrible decision, because I don’t have that kind of analytical mind at all.

When I was young, I was mainly writing poetry. And I loved it: I defined myself. And my poetry was very important to my mother; she was a great lover of poetry. I won some awards. When I was eighteen and in college, and very unhappy, I wrote one of those ‘teenage girls being unhappy’ novels. And then in my thirties the poems stopped coming. The lines stopped coming as poetry, and started coming as prose when they appeared in my head. And I had young children and I didn’t really write anything for a number of years. But whenever a line would come to me, it would come as prose. For example this line came into my head and it said, "My mother talked to us all the time." And I thought, well that is not poetry; at least it didn’t sound like anything that I could turn into a poem. But it sounded like the beginning of a short story, so I wrote a short story, and it was published in Redbook Magazine. The fiction editor loved it, and she said, "Oh, send us everything that you write." Well, that’s what you want. So I would write a story and I would send it, and they would always come back with the same note: “This story is wonderfully written, but it’s too depressing for our readers.” And by that time we were living in Oklahoma, where, if it was even possible, I was more depressed than I had been in college, and there was no way I could write anything that was not depressing. Which made, later on, George and Lizzie such fun to write, because it is not depressing, there’s wonderful humor in it as well.

One of my heroes certainly was Miss Whitehead, my librarian, Frances Whitehead, at the Parkman Branch Library in Detroit, Michigan. There were some teachers that I had in high school, an English teacher who was very supportive of me--two English teachers actually--who were very supportive of me; one of whom kind of mentored my poetry, so that was very meaningful. But mostly, the people that were the most important to me were the people in books. I think of Anne of Green Gables. I think of Jo March—I was a really big fan of Little Women, until Jo makes that terrible mistake and marries that old guy, Professor Bhaer. Terrible! And then there were all of the characters like the kids in Misty of Chincoteague. I really used books to escape, as I think a lot of people do.

My parents were very active in the Civil Rights Movement in Detroit, and that was something that was very important to me, and has continued to be very important to me. Just one example is that, because my mother worked, we had a housekeeper who became a part of the family, Mrs. Miller. We never called her by her first name. Even my father called her Mrs. Miller, and that kind of respect was very important to my parents, and has remained very important to me. As a librarian, my library growing up, the Detroit Public Library system, and even when I was working there in the late sixties, I thought was the ideal library. It’s funny, I still think of that library when I think about ideal libraries. So there was nothing in the library that I felt needed to be changed, except perhaps at that time when you checked a book out at the Detroit Library, there was a slip of paper, and you copied down the title of the book, they had these rules. So if it was a long title, that was a pain, especially if you had like ten or eleven books that you were checking out. And the other thing is that you couldn’t go into the Young Adult section or the Adult section of the library, which were separated from the Children’s section by a big circulation desk, until you were thirteen, and you would get then a special card with a green stripe on it that indicated that you were allowed to go there. And I remember that when I turned thirteen, Miss Whitehead took me over to the Adult section and introduced me to the librarians there, and they kind of welcomed me, and I checked out my first adult book, which was Gone With The Wind.

I spent about eight years in Tulsa, after my girls were in school, working and managing an independent bookstore. I had already gotten my Library degree from the University of Michigan, right after undergraduate, and when the bookstore was going through what seemed to be its imminent closing, one of the librarians from the Tulsa Library came into the bookstore, and I said, “Are there any jobs at the library these days?” And she said, “Oh yes, come in.” So I went in, and had an interview, and then met the manager of the central library, and was hired to work there, and then rapidly had a promotion and became head of Collection Development, which was a job that I really loved. But then the man who had hired me moved out to Seattle to be the Assistant Director here, and my younger daughter, had dropped out of college at the University of Chicago, and had moved out here to live a kind of wild and reckless life. She was here, and I came out to visit her, and of course saw my friend and his wife, and he said, “Well, what if I create a job for you at the library, would you come here?” And I said “Absolutely.” I mean, I was ready to leave Oklahoma. He just created this job, and I came and made it work. And my husband was a professor at Oklahoma State University, in Stillwater, Oklahoma. I said to my husband, “I’d really like to do this, but if you think this is not going to be tenable, then I won’t do it.” And, to his great credit, he said, “No, you have to do it. We’ll make it work.” So he stayed on in Oklahoma and worked for four years, and finished out his teaching so that he could retire with full benefits at the very young age of fifty three. And he’s lived off my earnings ever since, as I say to him.

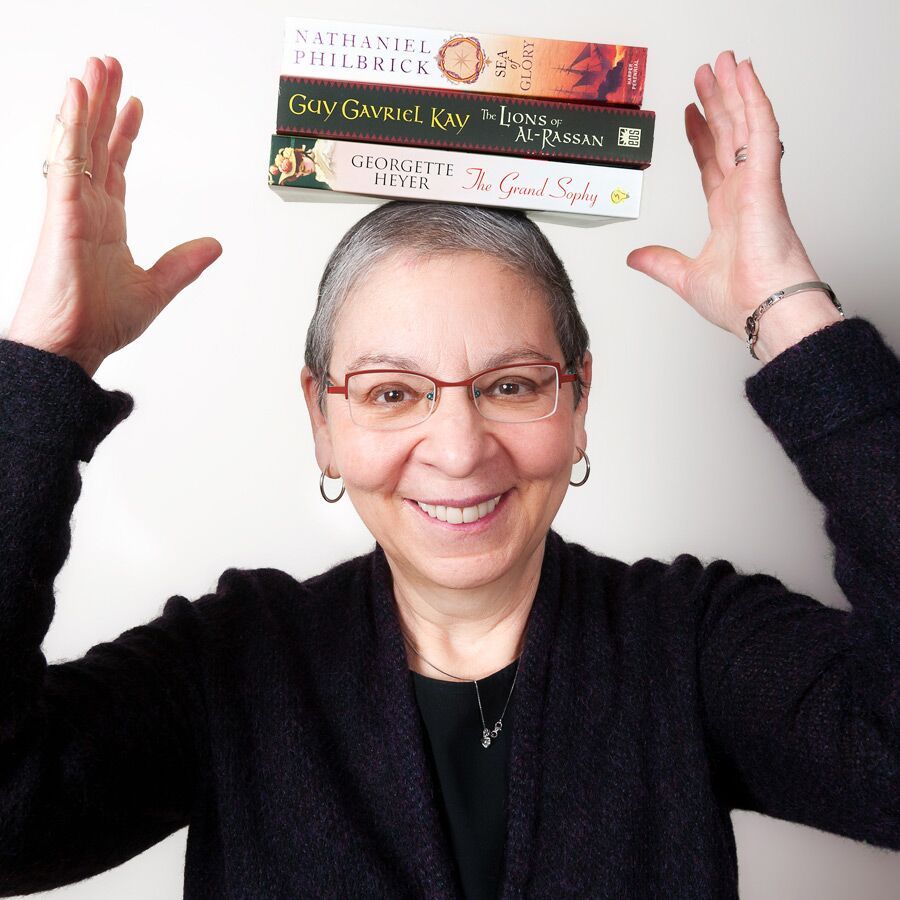

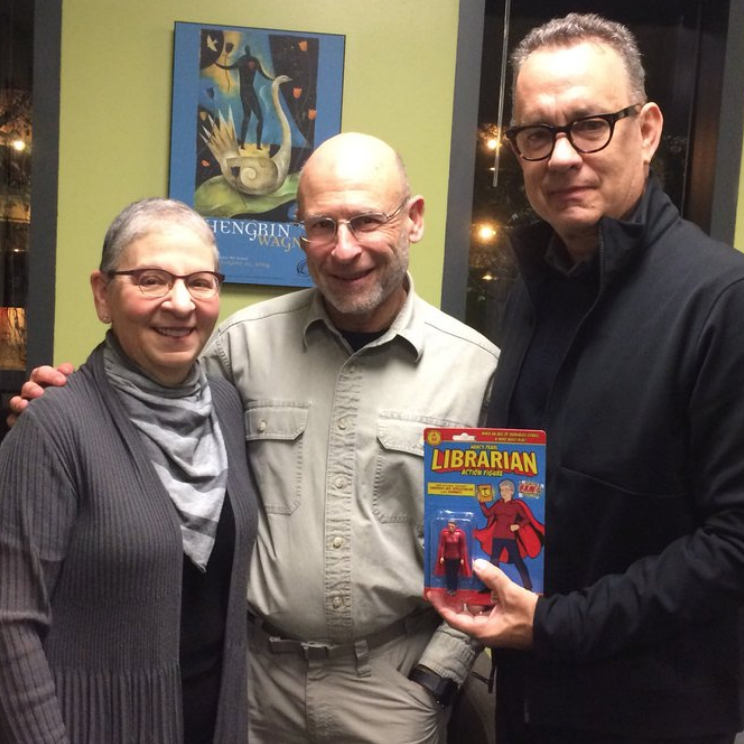

You know, it just happened. We talk a lot about making connections and the whole LinkedIn phenomenon, but it always has seemed to me that everything good that’s happened in my life has happened because of the kindness of others. So I came to Seattle in 1993, and in 1998, as a result of a grant from the Wallace Reader's Digest to fund, we started a program called “If All Seattle Read the Same Book,” and that kind of put the library on the map. And then, in about 2002, an editor at a local publishing company, Sasquatch Books, called me and said, “Nancy, come talk to me, I want you to write a book for us.” And so he described the book he had in mind, which was just that I would write about all my favorite books, and come up with quirky categories. I felt like I could go home and just sit down and get the thing done in a month. It took a little bit longer than that, but that became Book Lust, and it came out in the Fall of 2003. And then at the same time I was talking to Gary Luke at Sasquatch, my husband and I were at a dinner party with the owner of the Seattle company Accoutrements, which runs Archie McPhee, the store that has all those wonderful, kitschy, fun things. And he was telling us that they were making a series of action figures. He was saying that people were talking about the Jesus action figure and how it was performing miracles for them. He had gotten a letter or two about that. And I said, “But Mark, the people who really perform miracles are librarians. They change people’s lives every single day.” And somebody else said, “Oh, Mark, you should do a librarian action figure.” We all laughed, and then somebody else said, “And Nancy should be the model for it.” And then the conversation went on to many other things. And as we were driving home that night, my husband said his four favorite words to me: “Nancy, think this through. Do you really want to be a four-inch, plastic, non-biodegradable action figure?” And I said what I always say, which is, “Oh, it’s never gonna happen, why think about it? It’s not gonna happen.” And then it happened. So the librarian action figure came out, simultaneously, almost, with my book. Again, no planning. I mean, it wasn’t like we got this big marketing plan together. Just both came out early in September of 2003. And the librarian action figure’s action was a shushing action, which we all thought was great because it plays on that awful stereotype of librarians going, “Shhh!” Well there were, I would say, maybe thirty-eight or thirty-nine librarians around the world who had no sense of humor. And every one of them wrote to me: “You have set the librarian profession back twenty years.” So all of this controversy caused a Seattle writer to pitch a story to the New York Times about the librarian action figure, and the book, and me. And it ran in the Arts section, and then somehow, I am not clear on how this happened, I found myself sitting at the old headquarters of National Public Radio in Washington D.C., talking with people about reviewing books, or I call it recommending books. Which felt like a job interview, but they said “Oh no, this isn’t, we’re just talking.” And so then I started reviewing, recommending, talking to Steve Inskeep on air about books that I love.

Choosing books for the library

I think that when I was head of Collection Development, along with the Director of the library, I had great input into what books the library would purchase, and what books we wouldn’t purchase. And one of my strongest beliefs, is something that somebody printed on a t-shirt years ago: “There’s something in my library to offend everyone.” And that to me is the definition of a library. But when you’re asked to put books in the library that you have this strong, visceral reaction against, that you don’t want anybody to read for whatever reason, that’s when you have to step back and say, “This is the library. I have to put these books in the library.” Those are hard decisions. Like Madonna’s book, Sex, we did add it to the library collection. But we had people working at the library who opposed a book that showed nudity. That book would go into a desk drawer and never see the light of day. So where does that stop? But it’s more serious when you think about Holocaust deniers, for example. I have a Master’s Degree in History, so it’s particularly offensive to me, those false narratives about the Holocaust. Do those books belong in the library? Part of me says no, I don’t want anyone to read those books. Those books are not about history; they’re false narratives. And then part of me says, it’s a library. But that’s a hard decision. So I am torn, quite honestly.

I absolutely love those characters in the book: I love George and Lizzie immoderately. It was so interesting to write it because the characters came to me, just like my poetry used to come to me. They sort of appeared in my head and I would just write about them in little vignettes about their lives together and their childhoods, and things like that. But I can’t see how that’s going to happen again, because it was never anything that I had planned to do. I was perfectly happy reading other people’s novels and talking about them, or thinking about them. George and Lizzie were in my head for several years, but I only started writing it down when I couldn’t find enough books that I loved, and I just wanted to write a book that I loved—exactly the kind of book that I loved—and I did.

What I would really love to do is walk across the country and raise money for small and rural libraries. But the problem is that I’m not somebody who is at all capable of arranging things; I have really good ideas. So I’m just waiting for somebody to jump up and say, “I will get you sponsors, and I will arrange all that, and I’ll plot a route for you,” and do all that.

The future of physical books and libraries

Some days I am very confident that the physical book will endure well beyond any of our lifetimes. Some days I feel that the library has gone in so many other directions that the physical book will not, does not play as important a part in the life of the public library as it once did. But I believe that the library is the heart of a community, and that a community without a library is barely a community at all. What I believe is that reading makes us better people, and that the only way that we can gain a kind of understanding of other people, a sympathy for other people, is through reading and empathy. You know there’s a lot of talk about empathy and what it means, and how you instill it in children. Well, the best way to instill empathy in children or adults is to get them books to read that show them that people live in different ways. We spend so much time, in our society, inside ourselves, and the people that we talk to and the people that we spend time with generally think the same way that we do about “The Other.” I say that we always think we’re the Hamlets in our lives—you know, we’re the star of the show—but in reality, we’re really like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern: we’re the friends who come in and are killed off in Act V or whatever it is. We have to understand that, and we have to be able to look at the way other people live, and believe what they believe, and you get that from reading. And I think that it’s so important, now more than ever, that our leaders be readers. Books like Strawberry Girl, a children’s book by Lois Lenski, about the lives of migrant workers who travel around following the strawberry harvests: that book taught me about poverty. A book called Tree Wagon by Evelyn Sibley Lampman, taught me about Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. Everything I’ve learned, I’ve learned from books and reading.