I grew up in suburban Detroit. Actually, I was born in Detroit and then we moved just over the border, to a little suburb called Oak Park. At that time, it was probably about 80% Jewish. I’m the oldest of three kids and my parents—I think both of my parents grew up mostly in Detroit. My dad, definitely, and my mom, her dad was a doctor and they were living in Ohio, I think, during World War II, and then Texas. My dad was a CPA and my mom, she went back to college. She dropped out of college when she was 20 to marry my dad because she had been given the choice of a teacher or a nurse, neither of which were what she wanted to do. So, most of my childhood, my mom was going to college, and then grad school. She has a doctorate in 18th-century English criticism. She taught for a while, and then she owned a bookstore.

Anyway, I lived in Oak Park until I went to college at the University of Michigan. I graduated in the fall of 1975, tried to figure out what I wanted to do for a year or so, and then went to grad school for a year at Cornell in Ithaca, New York. I do languages, but it was actually there that I started doing radio. It was like an extracurricular activity. They had a campus radio station. I started working there, and I was really good at reading the copy without making a mistake. So, that’s how I became a radio person. I have no journalism background, it was all—well, I took some classes later—but most of it was on the job training. Because my degree’s in Chinese, actually.

I know more about my mom’s family than my dad’s family. My mom’s family are Russian-ish Jews—I don’t actually know where they’re from, and my mother was telling me that she can’t find anything either—and they fled the pogroms there. My mother’s mother was the fifth of eight kids, and the older two were born in Russia and the rest were born in the Cleveland area. My [maternal] grandfather’s family was also from somewhere around there, and they moved probably about the same time. Neither of my great-grandmothers spoke English. One prided herself on speaking Russian and the other one only spoke Yiddish. My dad’s family came in the 19th century, possibly from Poland, but nobody is sure from where. He’s related to a guy named Leonard Sillman, who was the creator of Your Show of Shows, with Imogene Coca, and Sid Caesar. That family, and most of those relatives, were sort of socialist-organizer kinds of people. My dad was the youngest of three boys, and he’s the only one who went to college in his immediate family. They both went to Central High School in Detroit, which was where all the Jewish kids went to school. Detroit has an immense Jewish population, compared to here.

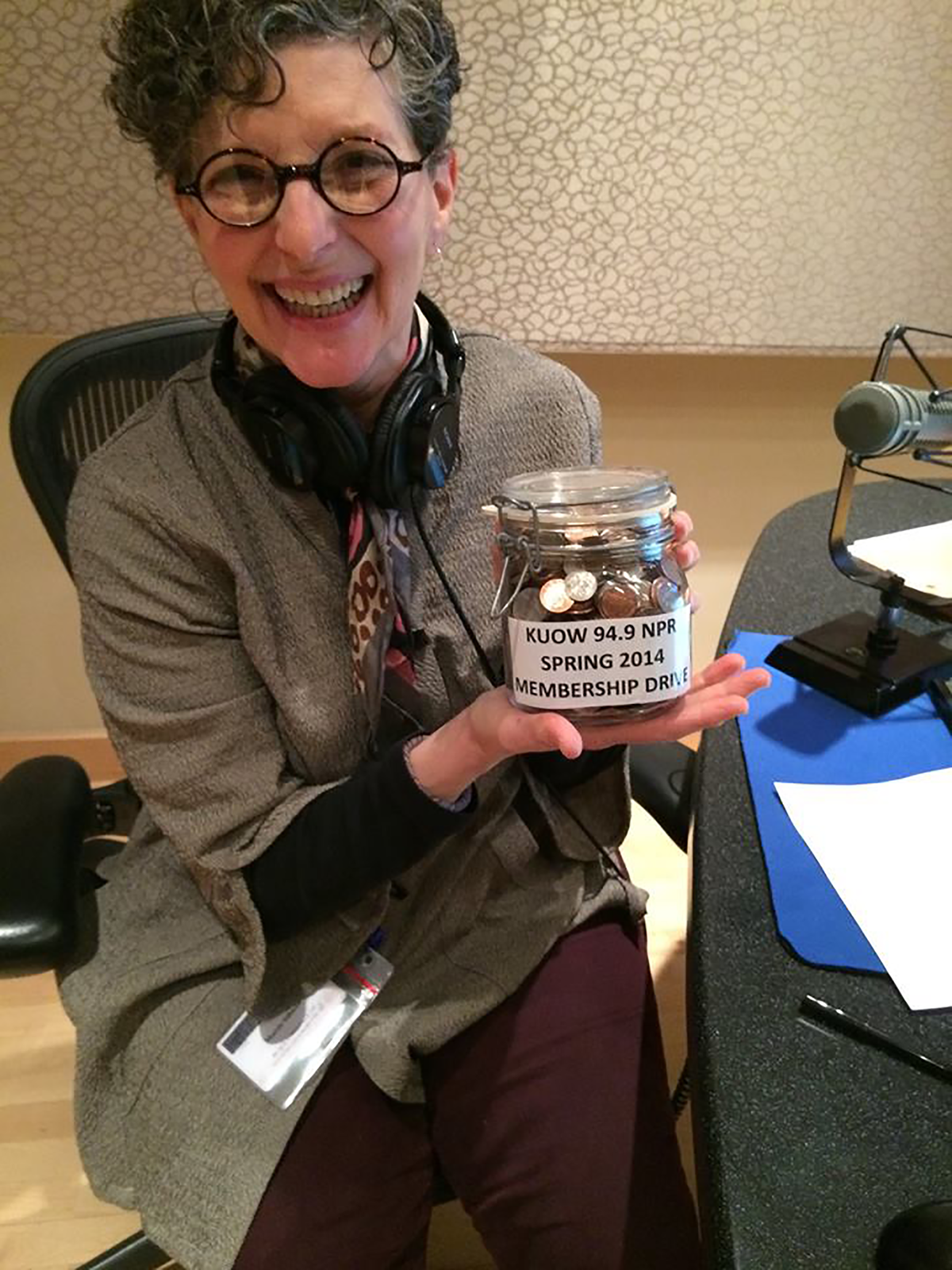

I was at Cornell from ‘77-‘79, maybe, and I had a housemate who was also an aspiring journalist. I finished my program and kind of dawdled around in Ithaca and then moved here in 1979. I wanted to keep working in radio. There was a community-owned station called KRAB—Krab Radio—and I started volunteering there. Within a year of that, I was working part-time at the university and taking journalism classes, because you can take classes if you’re a university employee. I took news-writing classes and production classes and then I got into a workshop that doesn’t exist anymore, in San Francisco, which was two weeks of sort-of immersion production. This was around 1980 or ‘81. I was volunteering at KUOW at that time and producing stories for a service that NPR had, called the Specialized Audience Module Service. I was reporting on the Southeast Asian refugees who were settling here. Then in 1982, I got a job at the radio station at Antioch College, which is in Yellow Springs, Ohio. I worked there until 1985; I was the Public Affairs Director and I taught classes there. Then I worked very briefly for WOSU, which is Ohio State University’s NPR station. Finally, due to a whole bunch of networking and people I knew, I got hired at KUOW in December of 1985, and I’ve been there ever since, doing a variety of jobs, for 32 years.

Changes she's seen in radio...

The Cornell thing that I did was actually a women’s show and when I first was doing radio, it was content about issues that affected women. That was really important to me. For the last 25 years, I’ve focused on the arts, which are undervalued. I’m helping with a graduate course at Seattle University and they’re mapping out innovative arts organizations between 1962 and 2012, and they asked me what had changed. I think the big change was that we’re starting to value community-based arts and cultural groups more than when I started doing this. I’ve really—for better or for worse—kind of identified with those two strands: women’s issues and the arts. I think maybe personally, I feel a little feistier than I do professionally. It’s just the context of working in that arena. You can advocate for subject matter or subjects that you want to profile, but you really are banging your head against the wall if you don’t stick to the format that’s been pre-approved and determined. I couldn’t just go out—bust things open. That’s why I wanted change. And things have changed. Our newsroom is predominately female. Although, maybe two months ago somebody was complaining about a male coworker of mine hosting the midday show, and they’re like, “Has there ever been a woman who has hosted a show?” And I said, “Yeah, me!” So, that was interesting. People have short memories.

...And changes she hopes to see

It’s interesting. I’m speaking from a vantage point of watching the network for a long time, decades. On one hand, I used to have to tell people it wasn’t a student station and that the network was a real thing. Now everybody knows NPR. And as NPR’s gotten better-known, I think it’s lost some of the distinctiveness that made its reporting so valuable to begin with. They had no reporters, so it was never about being first, it was always about being best. I think we’ve ceded a lot of really beautiful storytelling to podcasts, and I’d like it to be back on the radio. The reason I started doing this is because I fell in love with things that were coming out of my radio, and that was what I wanted to make. So, that’s what I would do. I would have more art on the air, of course. When I first started, there were two eight-minute segments each hour of Morning Edition that were reserved for arts reporting, and now you have to fight to get it on the air. I’d like it to be as integral as talking about what’s happening at the White House.

The evolution of the arts community in Seattle

It’s huge compared to what it was when I started. There was a man in town for a long time who passed away several years ago, Peter Donnelly, and he was very good as a catalytic agent and leader. We have a great head of the Office of Arts and Culture, Randy Engstrom. Jim Kelly, who’s run 4Culture at the county is stepping down, which makes me really sad, but we’re all stepping down. I think that they’ve been very good at leading and I think the challenges now are to bring a lot of voices to the table and to unify them going forward, in advocating for funds and advocating for their worth in this society. I think people have looked at arts and culture as an add-on and a frill as opposed to really the one thing that unites us all. Art at its best is a spiritual thing, the same as religion. To me, it is my religion. It forms communities and offers a place where we can find solace and shared something: shared vision, shared grief, shared joy. I don’t think that it gets that acknowledgement in the city or anywhere else in the United States, for that matter. And that’s what I want to see.

Thoughts on the #MeToo movement

That’s an interesting subject... I feel like the younger women I work with are like, “Why didn’t you guys say anything?” and I’m like, “Because we wanted jobs.” It is a huge thing when you talk about sexual harassment. We went around the room when we were prepping for a show; I was one of the last people to talk and at least twenty years older than everybody else in that room. And I said, “This is a manifestation of something bigger. It’s just the structure of our society.” It’s a society that really doesn’t want women in the workplace. I am often seen as the pushy bitch who wants stuff and is not afraid to ask for it. A lot of my younger coworkers will come to me if they want something. But, they’re all having babies and they have a lactation room. I did not have a lactation room when I had my son. So, I think they’re also optimistic that this is a turning point, and that everything is going to change. I hope that’s true, but I’ve seen things come and go and come and go. I hope it will result in some sort of awareness.

Frankly, I’m more concerned about pay equity and not having that. It won’t happen for me, I’ll be retired before there’s no longer a stigma for speaking out as a woman. I had a coworker say to me once, “You’re always complaining.” And I just thought, “Oh, white man…” He had a female producer who did all his complaining for him and she was tough as nails. It would be nice to be thought of as assertive rather than pushy, strong rather than bitchy. I would love to be around in a time when that happens. You know, Nina Totenberg, Cokie Roberts, and Susan Stamberg used to be called the Fallopian Triangle at NPR. It was so insulting.

Responding to criticism of public radio

Many years ago I was invited to the Stroum Center to talk to a group of women, and I got a lot of flack that NPR was too pro-Palestinian. I go to other places and in the left they say NPR is too pro-Israel. That tells me that NPR is doing exactly what it’s supposed to be doing, which is balanced coverage. I think our job is to tell the truth, and the truth is not black and white, the truth is murky. So, balance, I think we do balance. I don’t think there is such a thing as objectivity. I’ve never thought that. I think we are all very subjective beings, and our job, I was told this a long time ago, that my job is to represent anybody in the best possible light. That’s my job.

The women who’ve had to forge ahead. I've decided that Kay Graham is my role model after seeing The Post. I used to think it was Woodward and Bernstein, like every young journalist. That was who it was. I really admire Linda Wertheimer, Nina Totenberg, Cokie Roberts, Susan Stamberg, the women of my generation. It was hard for those women. They were at NPR because other networks didn’t really want them. Women who’ve pushed, particularly in journalism. My mom. I think those women.

Tom Cole is the Arts and Culture Editor at NPR that I have worked with since 1987, and he’s probably been my biggest mentor. If anybody taught me how to do what I do, it’s him. I didn’t start thinking of myself as a mentor until probably about eight, ten years ago, when I was in my mid-50s and I was like, “Oh, I guess I should tell somebody what I do, and how I do it.” If I’m working with somebody who’s enthusiastic, and a self-starter, it’s a good thing. I’m not very interested in just teaching in general. I don’t have patience for that. I’m happy if people want to learn and they have a lot of get-up-and-go, I’m happy to teach them, and I know it’s my responsibility to do that, since I’d like another generation of arts reporters to exist.

Impact of Judaism and Jewish values

My dad was an agnostic and my mom was much more religious. For me, the thing that stuck from Sunday school, besides the story of Purim and getting to dress up as Esther, was Esther, Naomi, Judith, all the women. The story of Naomi is like my favorite one in the bible. We also did a course in situational ethics that was very formative. I think, though, in a larger sense, it was about…it wasn’t so much about religion itself, although I celebrate all the holidays. It was about giving back, it was about tzedakah, it was about my responsibility to my community. That was something my father really illustrated to us, just by deeds rather than anything else. So, I feel very Jewish. I feel like I am, I don’t feel the need to go to a temple, because it’s the core of who I am. I had this conversation with my cousin about a year ago. None of us were very observant, but I think we all know who we are.

When I moved here in 1979, the Jewish community was mostly Sephardic. That’s who felt like had an identity here, and that’s who I seemed to meet. There was a deli on 15th on Capitol Hill, Matzah Mama’s, and I went in and I was like, “This is not a deli. This is not the real thing.” I felt like none of the signs of who I was were here. I felt like I talked too loud and used my hands too much. My very best friend is an Italian from New York, and we were both like two fish out of water. I think it’s partly not being born and raised here, but also just not finding the visible signs of myself in the community. I still feel like that a lot of the time here, because it’s just so…it’s so Christian here. Every year, when they put up Christmas decorations at work, I’m just kind of like, “Seriously? Not all of us celebrate this holiday.” I still have that conversation here. We did diversity training and I’m like, “Okay, so you’re all cool with race, but what part of the one when we were talking about religion did you not get?” I have one Muslim coworker, two now, and after the president was elected, we were sitting on a couch and I said, “Here’s the Semite couch.” I said, “I will register as a Muslim, if it comes to that.” And she said she would register as a Jew, and everybody looked at us. And I’m like, “Hello!” You know, “What about this don’t you get?” So I do still feel like an “other” here.