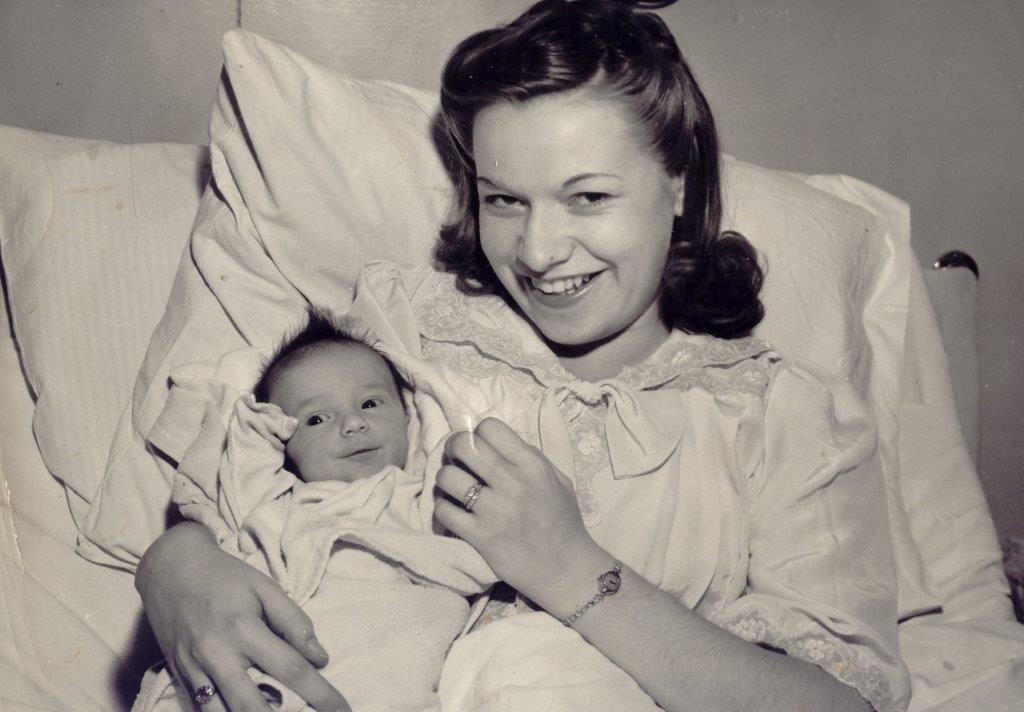

My mother's family emigrated from Ireland and Norway; my father's family came from what is now Czechoslovakia in the early 1900s. My father was originally from New Jersey. He was in Seattle during the war when he met my mother. I was born and raised in Seattle.

My family was Reform spiritually and observant culturally. I was raised with values of social justice, tikkun olam, fairness, hard work, family—all those kinds of Jewish values, absolutely.

I was the first in my family to go to college. I really liked being a student, and teaching was an opportunity to learn and make money. I didn’t feel called to K-12, so college teaching was where I headed. I graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in Political Science and went to the University of Michigan for a graduate degree. I was on track to complete a doctorate in Political Science with an emphasis on American government and a sub-specialty in judicial politics. I was always fascinated by law, but I didn’t know any lawyers and it was not something that I thought I could afford to do. But there I was, in Ann Arbor with a masters and a grant to do work for my dissertation on juvenile justice.

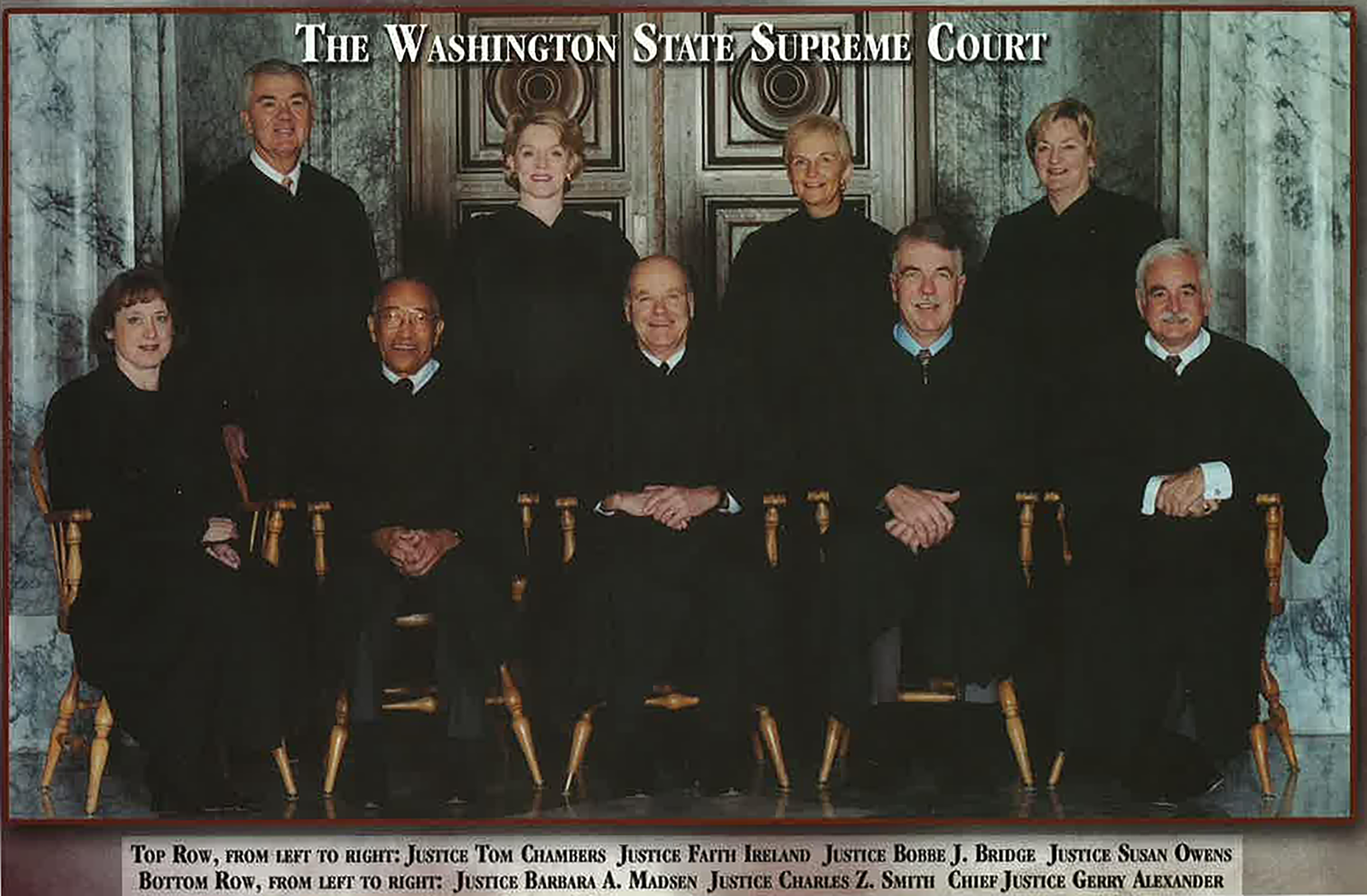

At that time, in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s, there was great deal of change being brought to the world of juvenile courts. Lots of different cases were being decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, the thrust of which was to introduce many of the adult criminal due process rights into juvenile court. Juvenile court didn’t look at all like most courts did in those days: The proceedings were in chambers as opposed to being out in a courtroom, there were no juries or lawyers, the judge frequently didn’t wear a robe, and the young person would be there with a probation officer (in the State of Washington, we call them “probation counselors”). The judge would presume that the child had done the crime of which he or she was being accused and proceeded accordingly to “fix” the child. It’s a social work model and one which the founders of the early juvenile courts in the beginning of the 20th century held dear. The idea was that children shouldn’t be treated like adults, which of course, science now tells us is exactly true, but their solution was to take them out of the adult system, because it was harsh at the beginning of the 20th century. By 1970-ish, people began to worry whether children were being treated fairly and why the presumption was not of innocence but of guilt. All of these rights were being introduced and there was a lot of turmoil which I thought would be very interesting to study, so I got a three-year grant to study juvenile courts in Walla Walla County and in King County. I interviewed and observed the stakeholders (judges, lawyers, and the kids themselves) as to how they felt about the proceedings, with my objective being to discern whether the introduction of these rights in King County had any difference on a kid’s attitude about how they were being treated versus the old way of doing things in Walla Walla County. During my study, I was introduced to lots of lawyers and got a lot of encouragement, particularly from one judge, Charles Z. Smith, who became a mentor for me. He was the first African American judge in the state of Washington. He encouraged me to get out of the back of the courtroom observing, and instead go to law school and become a lawyer. So I did! He was a great mentor to me then and carried through my years as a practicing lawyer. I ended up spending my first two years on the Washington State Supreme Court with him as my colleague.

Experiences as a woman in law school

Were things equal back then? No. Are things now? No. But I think that because of the women that came before me, I did have an easier path. I also had a wonderful law firm. It was very small, but it had a great sense of pride in giving back to the community. There was a culture of belief that being a lawyer was a privilege and we had the obligation to pay back to our community; there was a kind of tikkun olam spirit. Stan Barer had hired me, who I had first met in 1963 when I was a sophomore at the University of Washington. He was working for Congressman Brock Adams and I was taking a political science course, which required me to volunteer for some political campaign, so I chose Brock Adams. Stan and I had lost touch as he was in law school at the time when I was beginning undergrad, but during the summer of ’75 I was applying to be a law clerk. I got an offer from Garvey Schubert Barer, and it was Stan Barer who interviewed me—amazing coincidence—where I had the time of my life. I was the first woman who had been a law clerk at Garvey, and I ended up being the first woman associate and the first woman partner. It was a great experience and Stan is still a great mentor and one of my closest friends.

Move to the King Count Superior Court

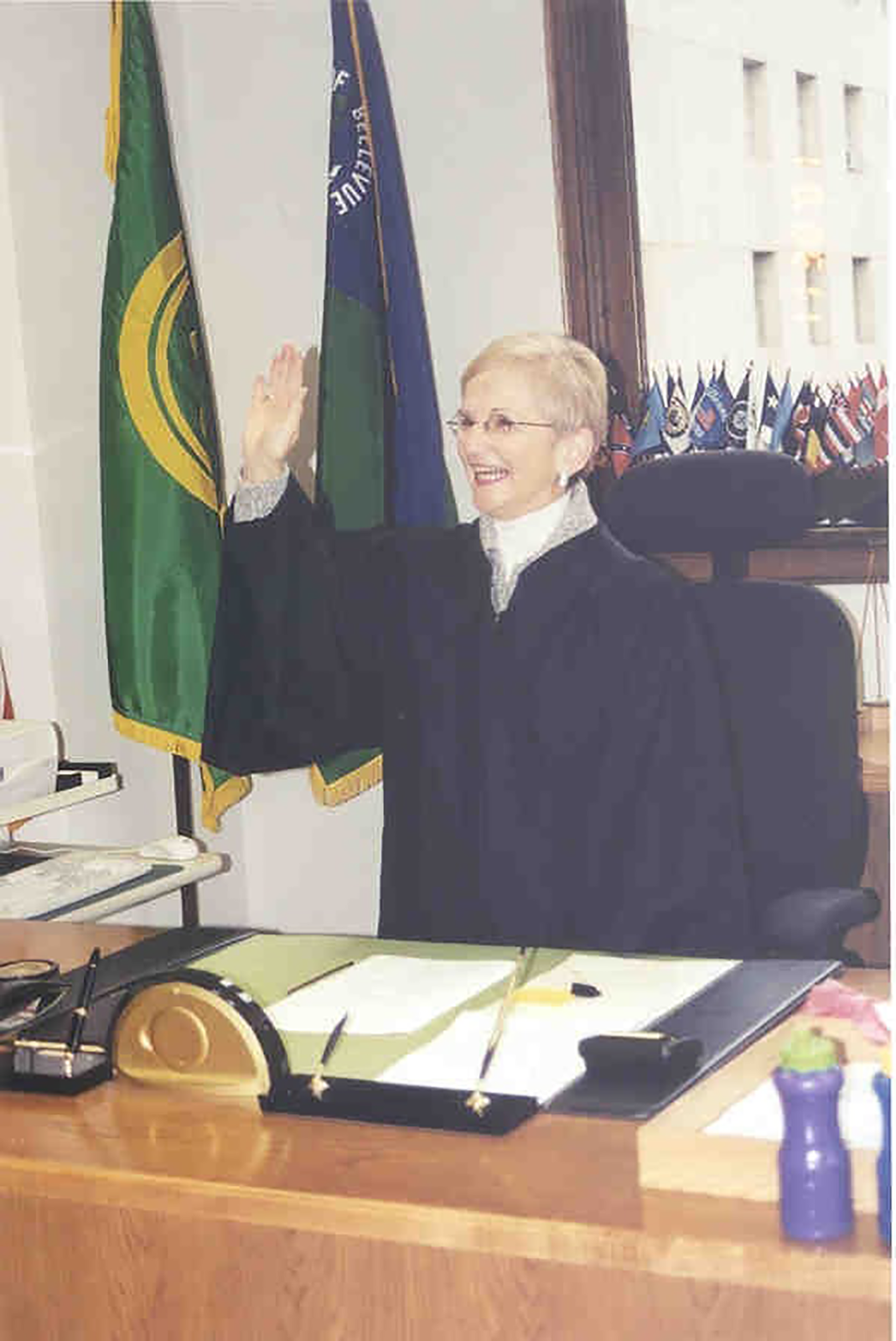

I was at Garvey for 14 years and then went to the King County Superior Court. I knew that I was ready to do something else. I indicated earlier that there was a culture at Garvey Schubert to be active in your community, which was unusual in the early 80s. I had a lot of experience doing board work, some of which reengaged me in the juvenile court issues. I got the itch to do public service full time, and in 1987 I was entitled to three months off through the sabbatical program at Garvey Schubert. At that time, I decided I was going to run for the King County council. I took on an incumbent and lost, but I realized that it was what I wanted to do. My mother-in-law and mentor Shirley Bridge said, “This may turn out to be a blessing.” She told me to stop thinking about the job, and just think about what I’m interested in and what I would like to accomplish. She was exactly right, because in spite of being a lawyer and kind of obsessive-compulsive about a lot of things, I’m not necessarily a person who plans everything. I wrote down a list of things and she looked at it and said I should be a judge. Over a couple of years, I got to think more about it. I spoke to friends of mine—women—who were judges and asked them how they liked it. Then I decided this was worth a shot—it circled back to my graduate school days of studying judiciary. I was selected by then Governor Booth Gardner for a vacancy that was left by John Riley, a judge who retired mid-term. He had said he had presided over too many trials where guns had killed or otherwise ruined the lives of everybody in the courtroom, so that he could no longer be objective as a judge and needed to be an advocate instead. I took his seat and loved every minute of my work as a trial court judge, and I felt very blessed to have had that opportunity; I was able to be an advocate for things that I cared about in the sense that I could improve the legal process as a judge.

I spent approximately four and a half years in juvenile court in the mid-‘90s, which was a very challenging time and not so different as to what’s happening now. At the time, juvenile crime rates were high and the mood of the body politic was to “get tough” on these kids regardless of their age. “Super-predator” was the terminology used by some social scientists, and there were a lot of harsh sentencing, statutes, and legislation being passed. For example, when it came to sentencing, the juvenile court judge typically had discretion—“individualized justice” was the phrase—not just a standard sentencing range, in which you couldn’t really deliver the right kind of package that would hopefully help this young person off the track of crime and on the way to a successful adulthood. A lot of that discretion was taken away from judges, with the idea that judges were too soft. Our code of conduct does allow us to speak on issues pertaining to the administration of justice. The Superior Court Judges Association of Washington created a legislative committee and I chaired it. We spent a lot of time on juvenile issues and we were at the table speaking from our experience—we were advising the legislators to take certain things into account, as “this is what we’re seeing” and “this is what we think is best.” So, I had a great opportunity to do all of that from a state-wide perspective through the Association of which I became president in the latter part of the 90s, right before I went up to the Supreme Court.

Washington State Supreme Court

That was one of those opportunities where I didn’t think that it was the right move. Unlike when I was contemplating the move from private practice, when I certainly had not learned everything I needed to know about the practice of law, but I had had the great opportunity at Garvey Schubert to do a variety of areas of law, so I felt ready. But this I wasn’t ready for. I thought I had a lot left to do at the Superior Court level and I enjoyed my work immensely. But Chief Justice Barbara Durham retired and left a vacancy on the court and then-Governor Gary Locke was accepting applications and letters of interest, and I was encouraged to go for the vacancy. I said to them that there’s no question it would be a great honor and a great opportunity, but I don’t think it’s me. But I thought about it more and said “Okay,” and Governor Locke agreed. The opportunity to get back to more of an academic posture, although it’s judging, it’s also learning, researching, and writing, so it’s a very different role than judging at the Superior Court level. But I was very blessed—it was a fabulous opportunity serving with Charles Z. Smith, and I learned a lot.

I’ve been a part of a formalized program for first year students at the University of Washington Law School since I was at Garvey Schubert, where they put together practicing lawyers and judges to mentor first-year law students. I’ve done that for years and I love it. Annually during the holidays, I host a lunch and bring everyone together. It’s particularly neat for the newest first-year law student to see what has happened with the others and show them that there is life after law school. It helps them to explore job opportunities and be in the right positions for internships as well as full-time jobs. It makes me feel good to be a part of it.

Pathway to the Center for Children & Youth Justice

I decided that I was not going to run for reelection in 2008. I thought about weaving together my experience, knowledge of the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, the network I’d developed (from Superior Court, Supreme Court, other branches of government, philanthropy, CBO, and community), and decided to return to my graduate school roots in juvenile court. I figured I had one more gig in me, so I thought about a variety of ways in which I could do that. I’d learned that the kids in the systems shared many of the same needs and experiences, whether they came in on the juvenile justice side or whether they came in through the door of child abuse and neglect. They were really the same kids and yet these systems didn’t talk to one another, they didn’t share resources, they weren’t learning from one another. So how could I bring that to an enterprise? I looked at a couple of models across the country, one of which was the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia, run by Bob Schwartz. It was focused originally on juvenile justice and later added some elements of child welfare. I thought that I could have the opportunity to do something similar.

We started the Center for Children & Youth Justice (CCYJ) in the beginning of 2006. In June of that year, CCYJ was selected by the MacArthur Foundation to lead and manage its Models for Change initiative (MfC) in Washington State. By the spring of 2007, we had developed a statewide plan for Models for Change—a plan forged with input from hundreds of professionals, youth, and their families from across the state. We were also doing work to improve the process and practice of addressing cases of children from birth to three-years-old in the child welfare system. In June of 2007, we announced the counties that had been selected to be our partners in Models for Change, and I announced that at the end of the year that I was going to retire from the Supreme Court to work full time at CCYJ. That’s how it all came together.

The Center for Children & Youth Justice is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit whose mission is to advance justice and improve the outcome for kids and youth who are in the juvenile justice and child welfare systems. We do that by improving those systems. CCYJ aims to make these systems more research-based and data-driven with respect to their interventions and relationships with these kids, so that they are focused on the kids themselves. We look especially at populations of kids who aren’t doing well after they had been touched by these systems. What I think CCYJ does best is bringing people together to learn how they might change a particular practice, policy, or legal process in the way that would improve that experience for kids and prepare them for future success. System professionals, educators, service providers, mental health experts, kids and families from these systems, all come together to learn how they can work more effectively on behalf of the kids and families in these systems. Sometimes the idea of “changing the policy practice process to make things better for kids” comes from research or experience, or sometimes it’s a replication of practice somewhere else where their numbers showed great outcomes for kids. We all learn together to see whether this could work in Washington. We help the professionals develop memoranda of understanding and documents they need to work together. We then either come with a grant or funding, or we help them to raise the funding in order to implement the new practice. Lastly, we manage them through a pilot. If we come out with good metrics, we’ve got success and we help them to sustain the new way of doing business.

We’ve applied this model in improving outcomes for LGBTQ kids, children who are survivors of sex trafficking, young people who have been subjected to group/gang violence, in both child welfare and juvenile justice systems. We’ve also applied the model to reduce the numbers of children and youth entering the juvenile justice and child welfare systems through re-engaging children and youth in school, providing legal assistance to families to keep them out of the child welfare system, and to reduce the numbers of youth and young adults from these systems who end up homeless.